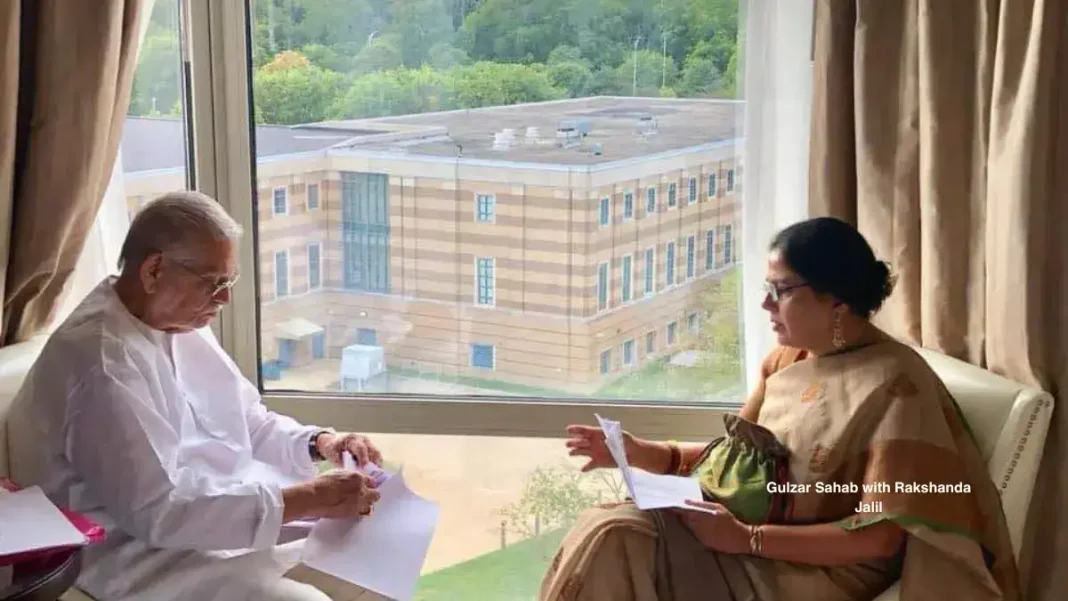

In the delicate art of translation, few challenges compare to capturing the essence of a poet as iconic as Gulzar. For Rakshanda Jalil, the journey was one of profound collaboration, where every word, pause, and metaphor was carefully molded to preserve the soul of Gulzar’s verses. With a steadfast commitment to bridging linguistic and cultural divides, Jalil’s translation work offers readers a rare glimpse into the heart of Urdu poetry through the lens of English. Together, they embarked on a poetic journey that transcended language, making each line a bridge between worlds.

1. Reading about you and your literary journey is indeed fascinating and inspiring. What was your experience working with Gulzar Saab like? How closely did you collaborate? Was the process highly collaborative? Were there any surprising, joyful, or challenging moments during your collaboration?

It was a very close collaboration. In fact, I have translated many people before but I have never found any other writer so invested in the act of translation. Let me share exactly how we have worked from our respective homes in Mumbai and Delhi. I would complete work on the poems in one book and email it to him. He, in turn, would do a very close careful reading, marking suggestions, comments, and feedback on each page. Once done, we would begin the process of going over each translation, line by line, word by word. For two hours every day, usually from 3-5 pm on weekdays, we would work on Facetime. Occasionally, when the connection was poor, we would switch to Whatsapp video. Every day, Gulzar sahab would be waiting, punctual to the dot, ready with his Urdu originals and my English translations open beside him. And this is how every single poem from the six books contained in this collected works was worked upon, face to face, line by line, word for word!

2. What challenges did you face, if any, while translating from Urdu and Hindi into English right from your first book till today?

I translate from Urdu and Hindi into English; these two languages have a very different register, a different kind of speech pattern, syntax as well as cultural vocabulary when compared to English. Perhaps if I were translating from Urdu to, say, Oriya, I might have fewer problems even though the two languages and the literatures associated with them have little in common. But since both Urdu and Oriya belong to the Indian sub-continent there are many things I can take for granted. It is not so with English. Apart from the purely technical aspects such as sentence structure, placing of verbs, the natural pauses in Urdu and Hindi, there is the huge issue of context. How do you translate cultural sensitivity? How do you translate something like jigar (literally meaning ‘liver’) which crops up repeatedly in Urdu poetry but is not used for liver in the anatomical sense? ‘Jigar’ is not even ‘heart’ (as when Ghalib says ‘Yeh khalish kahan se hoti jo jigar ke paar hota…’). For the Urdu poet jigar then is an abstraction and not a part of the human anatomy or an organ.

Elsewhere, there are images and metaphors that mean something automatically to those belonging to a certain culture. For instance, a kite with its string cut which is dangling from a banyan tree, the smell of the first rain on parched ground, the sweet scent of mogra blossoms in a bride’s sehra. The last image is especially poignant because the tremulous scent of mogra conjures up the bride’s tremulous beauty. Such images and metaphors that are rooted in a culture do not require translation when one is translating between Indian languages but when you are translating from an Indian language into English, you have one of two choices: burden your translation with explanations and make it cumbersome and clumsy; or retain the image and allow it to speak for itself and, when need be, give a detailed Introduction that sets out the contours of the context of your text.

3. What fascinates you about translating a collection of poems, musings, shayaris, or ghazals? How does this differ from translating other types of texts, in your opinion?

I have translated the Urdu poetry of Zehra Nigah, Kaifi Azmi, Shahryar, Javed Akhtar, and most recently Gulzar’s Collected Works. I think I have partly answered the challenges of translating poetry in the context of the differences in the cultural contexts of two languages as disparate as Urdu and English above. This is compounded by the fact that Urdu has natural pauses and silences which are understood by the Urdu reader. There is almost no punctuation in Urdu poetry. The other big challenge is the in-built rhyme and alliteration that can not be replicated in English.

4. Given your extensive experience in translating and promoting Hindi-Urdu literature, how do you see the role of translation in bridging cultural divides and fostering a deeper understanding between diverse linguistic communities?

Translations create bridges. They open windows into other literary cultures. They help readers rise above the picket fences of languages to look at literatures and their associated literary cultures that are different from their own. I do believe cross-fertilisation is very important for any literature. No writer can afford to sit on an island and remain insulated and cut off from what is happening in other literatures, especially in a country as linguistically rich and diverse as ours.

Losses are inevitable in the act of translation but, taken in the balance, the gains far outweigh the losses. A work of translation, it is said, is like looking at the wrong side of a carpet; the pattern and outline is clearly visible on the ‘wrong’ side but what is missing is the sheen and colour and brilliance of the ‘right’ side. Instead of being daunted by the losses, I do believe one should think of the immeasurable gains. For, if intrepid pioneering translators had not worked upon the finest of world literatures how much poorer our ‘own’ literatures would have been, to use an Urdu word how mehroom or bereft we would have been as readers.. Imagine not having read the Greek classics, the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Republic, imagine no Maupassant, no Russian Masters, no Gabriel Garcia Marquez, no Pablo Neruda either. Imagine, within India, not having read O.V. Vijayan, Mahashveta Devi, Vivek Shanbagh, Perumal Murugan and many, many others.

Check out our Latest Author Interviews

5. How do you handle words, concepts, or slang that might be considered “untranslatable”?

Yaar is one such example. I retain it as Yaar. I refuse to use Mate, Fellow, Buddy, Friend or any thing else that sounds too yankee, or too Australian. Similarly I retain the use of relationship terms such as Khala Jan, Chacha Jab, Amma, Abba, etc. I refuse to go by Uncle/ Aunt or Father/Mother. As a translator we need to keep pushing the envelope!

6. What advice do you have for aspiring literary translators? Are there any essential skills or qualities that one must possess to succeed in translating literature?

Read. Read. Read. Read other translations. see the experiments others are doing. Read translations from languages very different from yours. It’s an exciting world out there. There is so much to read and learn. The only essential quality is first and foremost, the ability read closely and faithfully. Only then can you translate faithfully and accurately. Keep your ego aside; keep it for your own writings. Humility is another essential tool. Remember the text you are translation is not yours; it is someone ‘s else’s. It can never be fully invested no matter how much of yourself you give to it.

7. In this book, Baal-o-Par: Collected Poems, can you pick your favorite two or three poems that intrigued and fascinated you?

I love the rain poems in this book. I love the images of trees holding up the hems (painchey utha kar) and walking about in the rain; the joys of an uncomplicated childhood and the deep gash on his psyche left by the partition; the moon and the night in all their majesty and mystery; the sun and day in all their toil and strife; the eye of an vortex that can gaze reflectively but also contain within it the possibilities of complete self-annihilation; the vastness of space with its many galaxies and distant universes of infinite possibilities; and God with whom Gulzar sahab has an easy, playful relationship as here:

‘O God, you must be feeling bad

I yawned

While praying!’

Or a contemplative one as here:

‘Having given form to a thought we searched for it —

The form that was a thought!’

In many of poems, the weight of the poetic experience rests on an image as here for instance:

‘I kept a lump of the moon’s sweet white misri on the palm of the astringent night

And pacified the displeased day’

Or in this sher:

‘The sky opens up at the mountain

Like a bale of cloth spooling out’

Images are deployed also to convey complex emotions such as this for communal riots:

‘Fire has a huge belly

It needs crisp, dry leaves every moment to munch on

Though it can also get by on a few twigs…’

Or this for Time:

‘Mother sat at the hearth rolling out Time

Waiting for the roti of Time to puff up

The impatient child

Turned the thali upside down

And played a game of “Night and Day, Day and Night”

Lest the glass bowl of the sky slip from his hand

Or the rice of stars fall from the thali

Mother Time placed a bowl of the moon in his thali!’

8. What is one of the most surprising insights you gained while working on your books?

Lets talk of the insights I gained from this book working with Gulzar sahab… Working with a poet while translating poetry has proved to be especially enlightening. A poet’s eye records words on a page differently; his ear is trained to hear words and cadences differently. I am no poet; my own non-translation work in English is entirely in prose. While I am aware that the syntax is different in prose and poetry, my eye and ear is not trained to switch seamlessly from one to the other. But working on these translations with Gulzar sahab, I have seen how knocking out a superfluous word here, a bit of flab there can tighten sentences. I have heard him make suggestions that lighten lumbering phrases, shorten long-winded sentences, and light up lugubrious and cheerless expressions. I cannot say I have learnt to write poetry over the past two years but I can say I have learnt the warp and weft, the taana-baana, of translating poetry. That too, from a Master!

9. A final question, why should anyone read Gulzar?

Let me answer with a question… Why should anyone read poetry? For the simple reason that it teaches so much about the world. shows us different ways of ‘seeing’. teaches us about the human heart.

Books are love!

Get a copy now!